Enter English resume of the issue

Wejście do prezentacji numeru w języku polskim

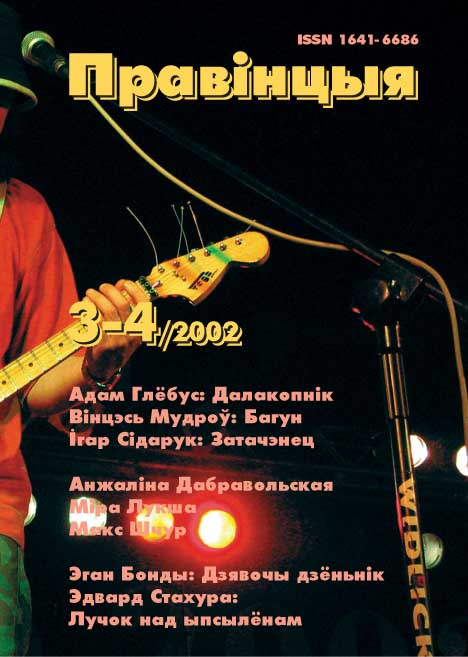

PravincyjaA Magazine of Literature and Art (in Belarusian)The Highlights of Pravincyja No. 3-4/2002The magazine is divided into three general sections that will also appear in subsequent issues:

words about wordsAlaksandar Maksimiuk, Basovišča: vyjście z anklavu (Basovišča: Breaking Out of the Enclave). The Young Belarus Music Festival Basovišča in Haradok near Bielastok marked its 12th anniversary this year. What importance did this annual event have for the young generations of Belarusians in Poland and their peers in the Republic of Belarus in the last decade of the 20th century? Is the life of an ethnic minority tantamount to confinement in an ethnographic museum? The text is copiously illustrated with excerpts from the Bielastok-based Niva’s reporting on different Basovišča issues and with many photos from 1990-2002.Nočču, ź lazom u rukavie (At night, with a blade in my sleeve). An interview with Krystyna Gromotowicz (Chryścina Hramatovič) — a young emigre from Bielastok now living in Philadelphia (USA) — whose translations of Polish and English poems are presented in this and previous issues of Pravincyja. Halina and Jan Maksimiuk talked with Chryścina Hramatovič during her short trip to Prague (Czech Republic) in 2001. The translator tells a fascinating tale of her odyssey from the Bielastok region to the „New World” and of how she rediscovered her path to the Belarusian language and her ethnic roots. Siarhiej Šydlouski, Prastora hieraičnaha (The Space of Heroes). „What is today’s land of Polacak if not the entire Belarus in its ethnographic boundaries? Take this idea away from the people of Polacak, and Belarus will be deprived of a thousand years of its history”, says the author in the opening of his essay. Polacak also boasts of being the hometown of Simeon of Polacak, one of the brightest minds in Belarusian history. How did Polacak shape its greatest writer? What influence does the historical heritage of this city have on today’s Belarusians? These are only a few focal points of this polyphonic text. Pravincyjnaja stalica (A Provincial Capital). An interview by Siarhiej Astrautsou with Taisa Supranovič, a writer from Navahradak. After publishing her debut book of prose, T. Supranovič endured several visits by KGB agents to her home and work. The only reason for such metings seemed to be the fact that her book was in Belarusian. The case of T. Supranovič is eloquently indicative of the situation of Belarusian literature in today’s Republic of Belarus. Besides the above-mentioned texts, this section contains the Polacak Diary by Aleś Arkuš and reviews of: a) Annus Albaruthenicus, a Biełastok-based annual literary magazine (by Siarhiej Šupa); b) Ihar Babkou’s book of prose Adam Kłakocki i jahonyja cieni (by Jan Maksimiuk); c) Biežanstva 1915 hoda, a book of memories (by Michał Andrasiuk); d) books of poetry: Leanid Hałubovič’s Apošnija vieršy, Jurka Hołub’s Poruč z daždžom and Michaś Skobła’s Našeście pouni (all by Jury Humianiuk); e) Aleś Arkuš’s collection of essays titled Vyprabavańnie razvojem (by Siarhiej Šydlouski). wordsVinceś Mudrou, Bahun. This short novel is another of the author’s private reckonings with history written in a brilliant literary style. September 1939, the invasion of Belarus by the Red Army, reprisals against „kulaks” and „enemies of the people”. All this is depicted not as a battle scene nor from a bird’s eye view, as our history schoolbooks taught us to imagine the war, but as seen through the eyes of the protagonist, an illiterate Belarusian peasant. Dramatic events of the novel are shown against an unobtrusively but confidently sketched background of anomalous social relations in the Polish-Belarusian borderland of pre-war Poland. A story in which the principal hero is a Belarusian can have no happy end.Ihar Sidaruk, Zatačeniec (Hermit). The life of a human being is more or less ruled by chance. Hryńka Skrypień is pursued by herds of women and, in spite of his genuine efforts to resist them, he always gives in. But when Hryńka sleeps with the wife of the town’s newly appointed police chief, events start to move faster. What shall the hero do to break free from the vicious circle of his sexual phobias? To seclude himself from the world? It will be enough to escape the revenge of the armed-to-the-teeth police officer. But can one escape the inferno of one’s own mind, one’s own morbid fantasies? This issue of Pravincyja also presents another Sidaruk story, Čykanuty (Cranky), which matches or even outmatches the first one in terms of its vibrant freakishness and convoluted plot. Adam Hlobus, Dałakopnik (Gravedigger). If there are people who bury the dead, there are also those who dig them out of the grave. This is the motto of the principal hero of this story, and it should be sufficient to recommend the story by the author who actually does not need any special promotion today. Giving this latest text of his for publication in Pravincyja, the writer apparently appreciated the effort of Bielastok-based Belarusians at translating into Polish his most renown book, Damavikameron, and at publishing the translation in 1998. Siarhiej Astraviec, Juhaslauski varyjant (Yugoslav scenario). After the Serbian opposition ousted Milosevic, political life in Belarus drew in a breath of fresh air. A speaker at one opposition rally even addressed the crowd in Serbian. Astraviec, a patient and punctilious annalist of contemporary Belarusian history, caught this and other moments with his characteristic irony and only half-veiled mockery. Belarus is not Serbia. Belarusians are not Serbs. In general, Belarus is not the best place for practicing American-style politics. Siaržuk Sokalau-Vojuš, Znak; Kanvoj (The Sign; An Escort). Two stories which are the fruit of the author’s travels to Italy and Egypt. Both are strongly permeated with Belarusian allusions, reminiscences, and digressions. The first prose publication by the renowned bard of „Belarusian Revival” of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Michał Andrasiuk, Pan Nosik (Mr. Nosik). How twisting the ways of love may be for a man of a mature age. Especially in a town so little that no secret can be hidden from people’s eyes and ears. The author seems to suggest that the Belarusian soul, oppressed by its urge to keep up appearances, is doomed to exalting eternal love to its native land rather than indulging in the sinful delights of the flesh. Siarhiej Rubleuski, Doždž u Stakholmie (Rain in Stockholm). What could we — ordinary and unpretentious people — add to the worn-out myth asserting that the Belarusian and Irish fates have much in common? S. Rubleuski makes his own attempt. This section also includes poems by Aleś Arkuš, Anžalina Dabravolskaja, Jaryna Dašyna, Vasil Dzivaševič, Jury Humianiuk, Mira Łuksza, Viktar Šałkievič, Maks Ščur, and Kanstatacyi (Assertions) by Siarhiej Abłamiejka. words for wordsIn this issue of Pravincyja the translation section is dominated by poetry. We present the three so-called poetes maudits of communist-era Poland: Andrzej Bursa, Rafal Wojaczek, and Edward Stachura. Polish readers need not be persuaded that these author are very important for Polish literature. For Belarusian readers, the translations from these three poets — along with those from Halina Poswiatowska presented in the previous issue — are intended to be an incentive to learn more about modern Polish literature.The present-day Polish literature is represented by Jerzy Plutowicz, a poet from Bielastok. Plutowicz’s poems — filled with a provincial aura and original intellectual reflection — place this unassuming poet from Bielastok in the front ranks of Polish literature and open before him the doors of the most renowned Polish literary magazines. All Polish poems were lusciously translated by Chryścina Hramatovič (an interview with the translator in this issue: Nočču, ź lazom u rukavie). Egon Bondy, Deník divky která hleda Egona Bondyho (The Diary Of A Girl in Search of Egon Bondy). A young Prague nympho goes out of the city, frees herself from her clothes, and sets out on a summer trip outside the Czech capital through picturesque fields and groves as well as the hills and valleys of central Bohemia. On her peregrination, she has sexual encounters with an impressive amount of tractor drivers, harvester operators, and ordinary collective farmers. In between, the heroine meditates on the philosophical foundations of human existence. This poetic provocation by Egon Bondy — a legendary figure of the Czech communist-era literary underground — can be regarded as one of the most vivid comments on the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and the subsequent „normalization”. Patrick Modiano, Villa Triste. Part 2 of 2. Part 1 of the translation was published in the previous issue of Pravincyja. The hero of this short novel, Victor Chmara, keeps groping his way among his memories crowded with mysterious characters and vaguely motivated actions. We witness the appearance of Villa Triste. But does this appearance shed any light on the hero’s life, which is shrouded in the mist of nostalgia? |