Enter English resume of the issue

Wejście do prezentacji numeru w języku polskim

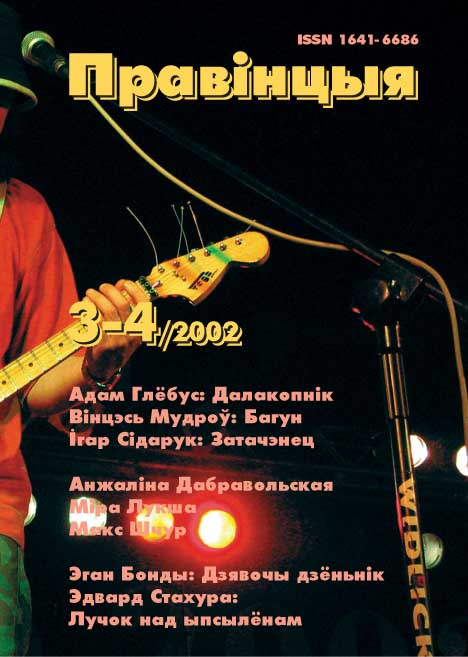

PravincyjaA Magazine of Literature and Art (in Belarusian)What is Pravincyja?Pravincyja is a literary magazine intended to present the contemporary Belarusian literature and art that are produced primarily beyond Minsk, the capital of Belarus. Pravincyja is published in two forms: a full-length hardcopy issue and an abridged Internet edition. The publisher of both versions is the Belarusian Union, a national minority organization based in Białystok, northeastern Poland, and led by Jauhien Vapa (Eugeniusz Wappa). The editorial team for Pravincyja’s first issue (No. 1-2/2000) consists of Aleś Arkuš (Połacak, Belarus), Editor-in-Chief Alaksandar Maksimiuk (Białystok, Poland), Jan Maksimiuk (Prague, Czech Republic), and Siarhiej Šupa (Vilnius, Lithuania). The publication became possible through a grant from Poland’s Ministry of Culture and National Heritage.„Pravincyja” (noun sing.) means „provinces” or „hinterland”. As in many other languages, the word in standard Belarusian has a rather negative connotation — it almost automatically suggests places that suffer from a measure of civilizational backwardness and intellectual narrowness, when compared with metropolises. When viewed globally, developments in provinces and capitals may fit such a pattern of assessment, but Belarus’s political and cultural situation in the postwar period has produced some significant aberrations from that assessment. There are three important reasons why the word „pravincyja” — at least with regard to Belarusian literature and intellectual life — should be given a more positive meaning than it has had so far. First, it became quite obvious to anybody in the 1990s that Minsk is essentially not a Belarusian but a Soviet city: its inhabitants had been heavily Sovietized as regards their everyday life and mentality, and Russianized as regards their language and cultural awareness. The communist authorities of the Soviet era sustained the city’s „Belarusian character” — by keeping Belarusian signboards on the streets and subsidizing some cultural activities based on national traditions — as a sort of make-up for their denationalizing policies. Perhaps the most important contribution of Belarus’s Soviet-era regime to maintaining the Belarusian national identity distinct from the Russian one was to provide financial support to literature in the mother tongue. Belarusian writers, of course, had to pay the price for that support. Most Belarusian poetry and prose of the Soviet period turned out to be only insipid and dreary exercises in political propaganda, and now those works are mercifully sinking into oblivion in musty libraries. Fortunately, despite the unrelenting censorship and ideological control, some Belarusian authors were able to produce books that continue to make an impression on the younger generations that reached their intellectual maturity after the collapse of the Soviet Union. What is peculiar about Belarusian literature is the fact that almost all of its authors were born outside Minsk — somewhere in the provinces — and drew on their „provincial experience” to make their names in belles lettres. Minsk was draining the provinces not only of a crude workforce but also from artistic talent. Minsk was feeding on the creative resources of the provinces but has not elicited virtually anything of literary importance from those born, brought up, and educated among its drab concrete apartment blocks. Since all of Belarus’s publishing houses and literary magazines were located in Minsk, it was possible to conceal the capital’s own impotence and sterility in national literature for quite a long time. When the regime of President Alyaksandr Lukashenka in the mid-1990s initiated its nationally and culturally debilitating policies of re-Sovietization and re-Russification in a suicidal bid to revive the defunct Soviet empire under the name of a „Slavic union”, Minsk finally became what it had painfully aspired to be for some 50 years — a nowhere place with all the inferiority complexes of a Russian provincial city vis-a-vis Moscow. Some of the most despairing Belarusian intellectuals even proposed that the Belarusian capital be moved from Minsk to a provincial town (for example, Navahradak) in order to prevent the concrete Moloch from devouring the „real Belarus”, which is purportedly embodied in provincial and country life. True or not, it should, however, be noted that many Belarusian regions (especially those in the country’s west and north) may be closer to „the heart of Belarusianness” than Minsk in the sense that their residents still speak Belarusian as well as follow some native traditions and customs in their everyday life. Belarusian intellectuals live in Minsk as they would in a foreign country. Minsk philosopher Valancin Akudovič has suggested that today’s Belarus be called the Archipelago of Belarus, arguing that on the political map of the Republic of Belarus the places where people speak Belarusian, develop Belarusian culture, or simply love their Belarusian Fatherland, form merely an archipelago of isles and islets in the sea of Russian language and culture. Well, if this gloomy metaphor fits the real situation, then of course the notion of Belarusian provincialism must be radically revised, at least because of its quantitative if not qualitative share in the area of the national archipelago. Second, the literary life in Belarusian provinces has experienced a sort of boom following the collapse of the USSR and subsequently that of the centralized system of allocating money and paper for the production of books in Belarusian. Many independent publishing initiatives appeared at the local level in the 1990s, and provincial publishers and authors have gradually begun to learn how to look for money for their books among non-state and private sponsors. Poet Aleś Arkuš from Połacak, along with his colleagues, set up the Association of Free Writers and launched the magazine „Kałośsie” in an attempt to coordinate the literary efforts of the provinces and provide a rostrum for disseminating the writings and ideas of those choosing to ignore the lines to Minsk publishing houses and literary periodicals. Belarus saw a group of interesting authors who were not only born outside Minsk (which is a norm in Belarusian literature), but also published outside Minsk and did not intend to move to Minsk. We may call this development a provincial literary revolt. Third, there is quite an unusual Belarusian region in Poland’s Podlasie Province (with Białystok as the main city). According to different estimates, the Białystok region, which stretches along the Polish-Belarusian border for some 200 kilometers, is inhabited by 100,000 to 250,000 ethnic Belarusians, who during the past half century managed to emancipate themselves from their disheartening status of peasant aborigines with hardly any historical memory to become a community with, more or less, a clearly defined Belarusian identity. Particularly notable is that the Polish Belarusians accomplished their ethnic transformation owing to exclusively their own efforts and resources. The authorities of the Belarusian SSR, which were working very hard to denationalize and Sovietize the main bulk of Belarusians, barred their citizens from any wider contacts with Poland’s Belarusian minority. They simply wanted to prevent the Soviet Belarusians from grasping that there may be a somewhat different way of national development for them besides Russification. Under such circumstances, Poland’s Belarusians could not even hope for any moral — let alone material — support from Soviet Belarus. The socioeconomic emancipation of Polish Belarusians has also given rise to literary pursuits by some three dozen Belarusian authors in Poland. The Belarusian-language literature in Poland may not be an event of international significance, but it is an important component of the Belarusian minority’s various activities and endeavors as well as a clear sign of its intellectual maturity and sophistication. Two literary magazines were launched by two Belarusian writers of the older generation at the turn of the century, including one published in half a dozen European languages (no kidding!). Among other Belarusian provinces, Poland’s Białystok region is by far the most dynamic in terms of the institutionalization of Belarusian activities. Some 4,000 children are still taught the Belarusian language at schools in the region, there are Belarusian programs on local public radio and television, a full-time Belarusian-language radio station in Białystok (believe it or not, the only Belarusian-language radio station on ethnic-Belarusian territory), and half a dozen minority organizations that fully enjoy the atmosphere of political freedom and pluralism in Poland, quarreling with one another much more often than collaborating. As some say, the Białystok region is a „Belarus in itself and for itself” (while being simultaneously part of Poland). Pravincyja is a literary project of the younger generation of Polish Belarusians who refused to build socialism under General Wojciech Jaruzelski’s rule and tried to ruin it jointly with their Polish colleagues. This generation had a lot of work to do in the early 1990s, when the freshly acquired democracy as well as the state course toward the European Union opened many possibilities (including job vacancies) for developing and deepening the ethnic identity of Poland’s Belarusian community. After a long string of political, economic, cultural, and educational projects within the Belarusian minority, the turn finally came to literature. The Polish-Belarusian border remains no less sealed than it was 10, or 20, or 50 years ago — but the Internet miraculously helps us contact inhabitants of the Belarusian Archipelago across the land and sea frontiers and share literary ideas and texts with them. |